‘May you live in interesting times’, it’s said, is a translation of a traditional Chinese curse. Sometimes, like the present, we discover we could do with less interesting times.

Apart from the usual, everyday litany of life’s problems in the modern world, a still raging pandemic is an ongoing reminder of living through an ever-enduring crisis.

Covid has so dominated our lives for over a year and a half that every other problem has been effortlessly pushed into the background.

But this summer a mountain of irrefutable evidence worldwide has conspired to bring climate change to the centre of the stage again, transforming it from an arcane interest of a few extremists to the growing perception that time is running out for planet Earth.

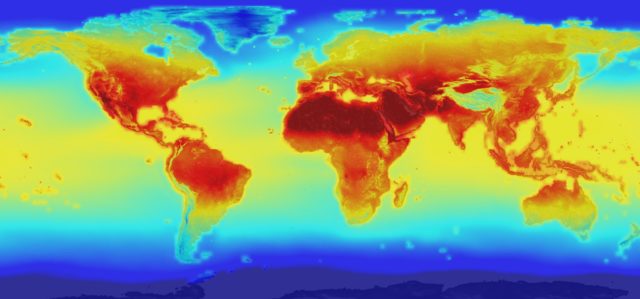

The evidence is incontrovertible: far-flung forest fires in California and Turkey; flooding in China and Germany; record temperature rises in Italy and Spain; warming seas dangerously consuming the polar ice-caps; and a series of other environmental catastrophes around the world.

All of this, suddenly happening within a few summer months, has focused our minds on an inescapable conclusion – our planet is on fire.

Compounding this reality is the timely report last week from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The stark conclusion is that our planet is in measurable trouble, it’s our own fault and unless we change our approach, disaster looms.

The damage can be reversed, of course, and great progress in terms of accessing and harnessing alternative sources of energy has already been made, but going the final mile will be both difficult and expensive.

Difficult choices face our planet. One is that countries – an obvious example is China – successfully transforming their economies by driving industrialisation and dragging their citizens out of poverty, are filling the atmosphere with carbon emissions from coal-fired energy which are damaging the environment.

The IPCC has specified in mathematical terms the price being paid in terms of rising sea-levels resulting from a refusal to change direction. While the levels may seem mathematically miniscule, the over-all result will be devastating, unless difficult choices are made now.

A recent Irish Times graphic gave a vivid representation of the major inevitable and irreversible climate changes that are going to take place unless a reversal in present policies takes place within a limited period of time.

It showed what the predictable rises in sea levels would mean for those living in Ireland’s most highly populated area, from Drogheda to Bray. For anyone living there or with family living there, it was a stark reminder of the high stakes involved.

The next summit on climate change to be held in Scotland in November may serve to focus minds on the need for action.

The word is that Pope Francis will attend, an indication of the seriousness with which he views the issue, a seriousness already demonstrated in his letter Laudato Si issued six years ago, one of the most impressive papal documents in living memory.

Francis had hardly found his feet in Rome when he assembled a number of worldwide authorities in climate change, including Fr Seán McDonagh, to help him research his now famous encyclical.

One of Francis’ reasons for writing Laudato Si was to inspire Catholic parishes to help raise consciousness of the impending crisis for humanity unless there was a clear and committed change in industrial policies.

Francis understood two things. One was that it was going to be difficult to convince mass populations of the need to make sacrifices that would involve a lessening of their incomes. A second was that a necessary building block for action was a process of ‘conscientisation’ – making people more and more aware of the deadly implications of climate inaction.

His great hope was that Laudato Si would be not just a clarion call for change but an opportunity for parishes to start the conscientisation process by encouraging local projects that would engage the support of the people. Unfortunately, apart from a few prophetically inspired initiatives, that didn’t materialise – even though, ironically, it’s probably the only issue in today’s world that engages the interest of the younger generation, now noted in religious terms for their almost universal disconnection from the Church.

Francis realised too that there would be voices raised suggesting that climate worries were not based on scientific data or were being exaggerated and that a counter-action was needed to address the climate change deniers, including some religious voices.

Just as pandemic deniers (including, to our shame, some religious voices) tried to underplay the seriousness of Covid despite the irrefutable evidence before their eyes, climate change deniers are already lining up to argue against the evidence not just of climate scientists but of their own eyes.

We are all part of the solution and probem regarding our climate crisis. The little steps we all take can lead to a collective and positive response to a brighter future.

“The universe unfolds in God, who fills it completely. Hence, there is a mystical meaning to be found in a leaf, in a mountain trail, in a dewdrop, in a poor person’s face. The ideal is not only to pass from the exterior to the interior to discover the action of God in the soul, but also to discover God in all things.” Laudato Si (Paragraph 233)

SEE ALSO – Work set to begin following €190,000 investment in Portarlington tourist location