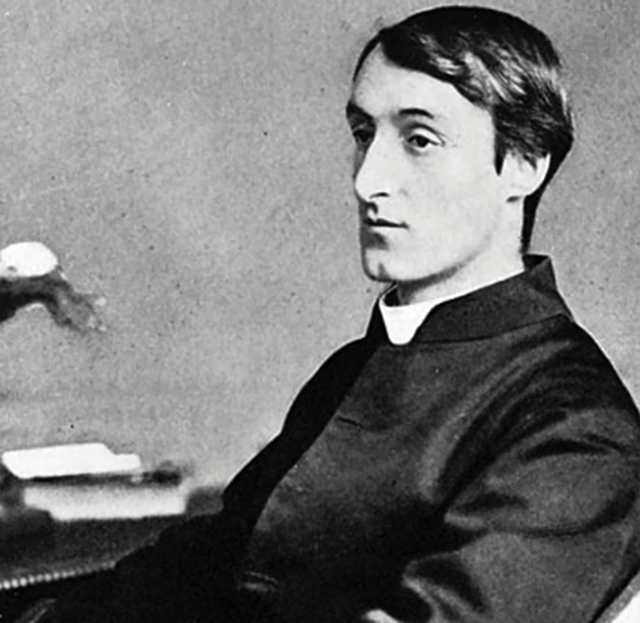

2017 marks the 30th anniversary of the Hopkins Summer school, taking place in Newbridge College, from July 21-27. This is an occasion for many poetry lovers to gather and celebrate the remarkable inspiration offered by Hopkins. A poet, whose inner turmoil and spiritual hunger gave birth to some of humanities greatest poetic works.

Like many other poets, the importance of Gerard Manley Hopkins poetry was not made clear until after his death, with the posthumous publication of most of his works. He is now widely regarded as one of the most important poets of the Victorian era.

Born in Stratford, Essex in 1844, Gerard Manley Hopkins was the oldest of nine children, with devout Anglican parents. An artistically-minded family, many of Hopkins siblings were musicians and painters, and he himself developed a love for poetry like his father from an early age.

In 1852 Hopkins’ family moved to Hampstead, and at ten he was sent to board at Highgate School, with his earliest known poetry dating from his time there.

After school Hopkins attended college at Oxford, where he studied classics. While here, he read John Henry Newman’s Apologia Pro Vita Sua, in which he describes his reasons for converting to Catholicism.

Two years later Newman himself received Hopkins into the Catholic Church. This decision caused estrangement with some of his family and friends.

In 1868 Hopkins decided to enter the Society of Jesus; before entering the noviciate he made a bonfire of his poetry, determining to give up writing altogether. He studied at Manresa House and then at Stonyhurst in Lancashire.

In 1875 while studying in a Jesuit house in north Wales, Hopkins was asked by a superior to write a poem about a German boat recently shipwrecked in a storm. After seven years of abstinence, Hopkins took up his pen and wrote The Wreck of the Deutschland.

This work featured a rhythmic technique called sprung rhythm, a structuring he invented which would go on to shape not just his own later works but those of a whole generation of poets that followed him.

To that point, English poetry followed the rules inherited from Latin languages, where lines were defined by the number of syllables. However the qualities of the English language are such that Hopkins found focusing on the stresses rather than syllables within a line to be the optimal basis for composing poetry.

Radical

Deemed too radical, Hopkins’ poem on the sinking of the Deutschland was refused for publishing, an act which further disheartened him, though he continued to write poetry afterwards. After his ordination as a priest in 1877 he moved around England, acting as curate in London and Oxford and teaching in Chesterfield and at Stonyhurst College.

In 1884 Hopkins moved to Dublin where he was made professor of Greek and Latin at UCD. Living away from friends and family in a city full of political strife, Hopkins did not enjoy his time in Ireland, feeling isolated and alone, often suffering bouts of depression.

The poetry written around this time reflects this, in what are known as the ‘terrible sonnets’, terrible for the pain and hopelessness evident in them. He died in 1889 of typhoid, at the age of forty four, and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. Few of Hopkins poems were published during his life.

It was not until after his death that his poetry was released by his lifelong friend Robert Bridges, and it began to receive the acclaim it was never given during his lifetime.

As Kingfishers Catch Fire

As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame;

As tumbled over rim in roundy wells

Stones ring; like each tucked string tells, each hung bell’s

Bow swung finds tongue to fling out broad its name;

Each mortal thing does one thing and the same:

Deals out that being indoors each one dwells;

Selves — goes itself; myself it speaks and spells,

Crying Whát I dó is me: for that I came.

I say móre: the just man justices;

Keeps grace: thát keeps all his goings graces;

Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is —

Chríst — for Christ plays in ten thousand places,

Lovely in limbs, and lovely in eyes not his

To the Father through the features of men’s faces.

– Fr Paddy Byrne

SEE ALSO – Fr Paddy: Mother Teresa… an icon of love